I Heard You Like Choice, Here’s 50: The Obamacare Marketplace

In the United States, we have Medicare for seniors and the disabled, Medicaid for the needy and to supplement Medicare, the VA for the military and veterans, the Indian Health Service for natives, and employer insurance for people that work for large enough employers or employers that choose to offer it. For everyone else (primarily the self-employed and people without employer offers), we have the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces, also known as Obamacare. In what follows, I will try to explain how the Obamacare marketplace basically works and for whom.

Health Insurance Coverage in the US

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2019, 14.2% of the country was covered by Medicare, 19.8% by Medicaid, 1.4% had military coverage, 49.6% had employer coverage, 5.9% had non-group coverage, and 9.2% of the population was uninsured. With the effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), that has changed somewhat. For example, 82 million people (almost 25% of the population) are currently on Medicaid. And while typical Obamacare marketplace enrollment was closer to 11-12 million from 2015-2020, 14.5 million are enrolled this year with an additional 1 million being covered by Basic Health Plans after the introduction of ARPA Subsidy enhancements. A significant number of people also purchase insurance off the ACA marketplace for themselves which do not qualify for subsidies and are not held to the same standards as ACA insurance. Insurance off market is closer to the insurance market prior to the ACA.

Employer Insurance

You can’t really understand whom Obamacare serves without understanding what hole it was built to fill, the people not covered by employer insurance. Aside from many people already having employer insurance prior to the ACA (it’s been the main insurance scheme for 70 or more years now), the ACA designed two things: the Employer Insurance Mandate and the Employer Insurance Firewall.

Employers with more than 50 full-time equivalent workers (defined as working 30 hours per week) are required to offer 95% of their employees and their dependents “affordable” health plans that meet a minimum standard of quality. Spouses are not considered dependents and coverage offers are not required for them. Children must be allowed to stay on their parent’s plans until 26, the plans must at least have an actuarial value (roughly cover the costs) of 60% of health spending for the total enrolled population, and the employee share of premiums are only “affordable” if they are less than or equal to 9.83% of wages for individual coverage. Wages are determined by wages earned after withholding 401k contributions or monthly pay, and the employee share must not exceed the poverty line for an individual for the sole employee’s coverage.

There are several different penalties for employers that do not meet these standards. If no coverage is offered, the employer must pay a $2,700 penalty for each person not offered coverage minus the first 30. If the plans do not meet a minimum value or aren’t “affordable”, then employers must pay the lesser of ~$4,000 per full time employee on the Obamacare marketplace or $2,700 per employee not offered affordable coverage past the first 30. However, these penalties do not seem to have changed employer behavior, as seen below.

(Taken from: here.)

The “Employer Firewall” is the employee side of the equation. If an employee receives an “affordable” offer from their employer, then they cannot qualify for Advance Premium Tax Credits (APTCs) to purchase Obamacare. They need to take the employer offer, purchase insurance without government help, qualify for Medicaid, or go uninsured. Furthermore, employers don’t have to offer coverage for essential health benefits, only some preventative care. And the minimum standard is similar to a Bronze plan even though the benchmark plan in Obamacare is the second cheapest Silver Plan. This traps some low wage employees with inadequate insurance when they could find better coverage on Obamacare. Finally, coverage only needs to be affordable for the individual and not their children or spouse, but the Biden Administration is proposing a rule to fix this problem.

The Small Group Market and Individual Market Hybrids

Even outside of the employer mandate, the market is further split into two groups, the small group market and the individual market. For businesses with less than 50 employees (several states have expanded this to include businesses with up to 100 employees), they can purchase insurance plans on the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP). Businesses can also apply for a tax credit if they have less than 25 employees and meet other standards. But remember, this program is voluntary and businesses with less than 50 employees are not required to offer coverage.

More recently, there’s also a program called Qualified Small Employer Health Reimbursement Arrangement (QSEHRA) where businesses with 50 or fewer full time employees can set aside money each month for employees to purchase their own insurance on the individual marketplace or use it on other medical expenses. This was created as a provision of the 21st Century CURES Act in 2016 as a response to employers not affected by the employer mandate leaving the employer insurance market. In 2019, the Trump Administration created Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangement (ICHRA), which allows larger employers to opt out of employer coverage if they help employees purchase insurance on the individual marketplace with aid at least as good as employer mandate standards. However, they can’t mix and match. They either have to go all in on employer coverage or the individual marketplace. As of 2022, between 100,000 and 200,000 people are covered under this scheme.

Obamacare

This brings us to the Obamacare marketplaces. For people without employer insurance or some public plan, they have to shop for their own plan. The individual market existed prior to the ACA, but the ACA marketplace regulated it with a much greater degree of scrutiny. Prior to the ACA, people on the individual market could be denied coverage for pre-existing conditions, lifetime limits on coverage existed, and insurance companies were allowed to go through lengthy review processes assessing your health prior to coverage. This makes some sense from an actuarial point of view, the sicker you are, the more you can be expected to use health insurance. However, this had the effect of locking out the sick without employer coverage or public plans from having any coverage at all. And many people didn’t sign up for coverage because of the cost or difficulty in applying.

The Obamacare marketplace was designed, much like the Medicare Advantage, Medicare Part D, or Medicaid Managed Care markets, to allow for a single source to shop for plans. States could either rely on the federal website, Healthcare.gov, or design their own. Here’s a current map of what states design their own or rely on the federal government.

Open enrollment on the federal website takes place from November 1st each year until December 15th, with plans going into effect on January 1st. The President has some discretion to change this. People can also sign up if they qualify for a “Special Enrollment Period” such as losing a job or some other gap in coverage, but if you neglect to sign up you may need to wait a year until the next enrollment period. You will also be disenrolled for failure to pay premiums. Plans on the Obamacare market cannot deny people for pre-existing conditions, and are prohibited from assessing health status except for asking if enrollees smoke. They are also prohibited from charging people different premiums except for age or smoking status. People who admit to smoking can be charged as much as 50% more than non-smokers (varying by state). Enrollees ages 0-14 are charged the same rate and enrollees ages 15-20 increase on a yearly basis. The age band is calculated at a ratio of “1” for enrollees aged 21, and the ratio steadily increases until hitting a ratio of “3” for every aged 64 and older. In other words, if a 21-year-old is charged $4,200 per year people aged 64 and older can be charged $12,600 per year, while people younger than 21 are charged slightly less. Rather than being uniform, the ratio increases slowly before speeding up rapidly at older ages, though this varies by state. States are also allowed to use different age bands, and Charles Gaba of ACASignups.net has a more detailed explanation here. Premium costs also vary by region within each state.

Plans are also somewhat standardized regarding benefits. Preventative care must be free and there is a list of “essential health benefits” that all plans must cover. Plans also come in four metal levels: Bronze, Silver, Gold, and Platinum. These plans roughly cover 60%, 70%, 80%, and 90% of costs, respectively. There are also “Catastrophic” plans that cover essential health benefits and a few primary care visits each year. However, these plans are only available to people ages 30 and younger or if you have a hardship or affordability exemption like being in the Medicaid gap. Catastrophic plans are ineligible for Obamacare subsidies as well.

To ensure plans are spending money on care, the ACA set up a Minimum Loss Ratio of 85% for large employer plans and 80% for other plans. If less than that percentage of expenses were spent on patient care, insurers have to send enrollees a check for the balance. This is imperfect, and some people criticize how insurers spend money to meet the MLR threshold.

The government mandating guaranteed coverage and charging the same amount regardless of health status creates a problem of adverse selection, incentivizing sicker people to enroll while disincentivizing the healthy. This would lead to progressively more expensive health insurance, causing spiraling costs until the market crashes. Employer plans avoid this by mandating offers, subsidizing enrollment with tax preferences, having a waiting period before enrollment, and having a risk pool among employees. Obamacare attempted to address this with limited enrollment periods, the individual mandate, subsidies, initial reinsurance to compensate expensive care, and risk adjustment. The individual mandate was set to $0 in the Trump Tax Cuts, but risk adjustment remains. Healthy people may have an incentive to search for cheaper off-market plans, or the cheapest Obamacare insurance possible, while sicker patients may gravitate to more generous plans. Risk adjustment sets up transfers between plans both on the Obamacare marketplace and off the marketplace using risk scores of enrollees. This requires plans with disproportionately healthier enrollees compensate plans with sicker patients, making adverse selection more difficult. This process is complicated and the devil is often in the details.

Because of guaranteed issue and the age band, unsubsidized plans can be quite expensive. Many people are used to seeing plans subsidized by the government, or their employer. That’s where the Obamacare premium subsidies/APTC and Cost-sharing Reductions (CSRs) come into play. The APTC is calculated using the cost of premiums for the second cheapest Silver plan available to the enrollee and their income. Enrollees can then take their APTC calculated by the formula and use it to purchase any plan they want. The original formula for the ACA premiums post-subsidy and the formula post-ARPA are shown below.

(Taken from here.)

As you can see, the original ACA only offered APTCs to people making from 100% of the poverty line to 400% of the poverty line, stopping at 9.83% of income to match the employer mandate. That was called the “subsidy cliff”, and that could drastically increase the cost of Obamacare for older enrollees. ARPA subsidies were extended such that the second cheapest Silver Plan would never cost more than 8.5% of income. If you make less than the poverty rate, then you are ineligible for subsidies and must enroll in Medicaid. That’s reasonable enough for someone in a Medicaid Expansion state, but 2.2 million people currently trapped in the “Medicaid Gap” in non-expansion states. This was caused when the Supreme Court ruled in Sebelius v. NFIB (2012) that the federal government could not withhold Medicaid funding if states did not choose to expand Medicaid. This made the Medicaid Expansion voluntary instead of de facto mandatory, and 12 states still haven’t expanded Medicaid. An interesting asterisk to the “Medicaid Gap” is it does not apply to lawfully present immigrants that are not yet eligible for Medicaid because they have been in the US for less than five years.

Premiums aren’t the only cost in insurance though. There are also copays, coinsurance, deductibles, and the out-of-pocket maximum. Even if you can afford the premiums, the care might be too expensive. That’s where CSRs come in. For people making from 100% of poverty to 250% of poverty, Silver plans must offer lower copays, coinsurance, deductibles, and out-of-pocket maximums. This increases the actuarial value of Silver plans for these enrollees to 94% for people making between 100%-150% poverty, 87% for 150%-200% poverty, and 73% for 200%-250% poverty. This only applies to Silver plans, so people under 250% poverty may counterintuitively get better coverage on Silver plans than Gold or Platinum plans. CSR funds were paid by the federal government prior to 2017. Technically, there was a legal argument about whether these CSR funds were appropriated by Congress in the ACA. The Trump Administration used this to remove CSR funds as an attempt to sabotage the marketplace. However, this created a glitch called “Silverloading”. Essentially, insurers were mandated to offer the benefit, but the federal allocation was gone. Either insurers could raise ACA premiums for all plan types, or they could exclusively raise silver premiums. The APTCs were calculated by the cost of the second cheapest Silver plan, so if insurers only increased the premiums of Silver plans, this would increase APTCs to enrollees and give them more money to use towards Silver plans to offset the cost. Enrollees could then use the money to purchase other plan types. Post-subsidy, this could cause other metal levels to be even more affordable at greater cost to the government. This would incentivize people making more than 400% poverty to purchase other metal levels to avoid the price hike in Silver plans, but it avoids hurting all enrollees if insurers raised premiums across the board. Some states like New Mexico and Texas are now legally mandating Silverloading to exploit this glitch.

So, who’s covered by Obamacare?

Like I mentioned above, Obamacare is essentially the system we created for people too high income for Medicaid, too young and healthy for Medicare, not in the military, and not offered an “affordable” employer plan. According to The Commonwealth Fund, 1.4 million Obamacare enrollees were self-employed or small business owners (1 in 5 enrollees) in 2014. And more than 10% of gig economy workers got their insurance through Obamacare. They estimated that of the roughly 63 million Americans self-employed or employed by businesses with less than 100 employees, 15% (~9.5 million) were in the individual marketplace and abut 5.8 million were in the Obamacare marketplace of the 11.1 million Obamacare enrollees. The rest were either covered by an employer plan, covered by Medicare or Medicaid, enrolled in a non-compliant off market plan, or uninsured. Many other Obamacare enrollees likely include spouses and children. In total, just over half of Obamacare enrollees own or work for a small business.

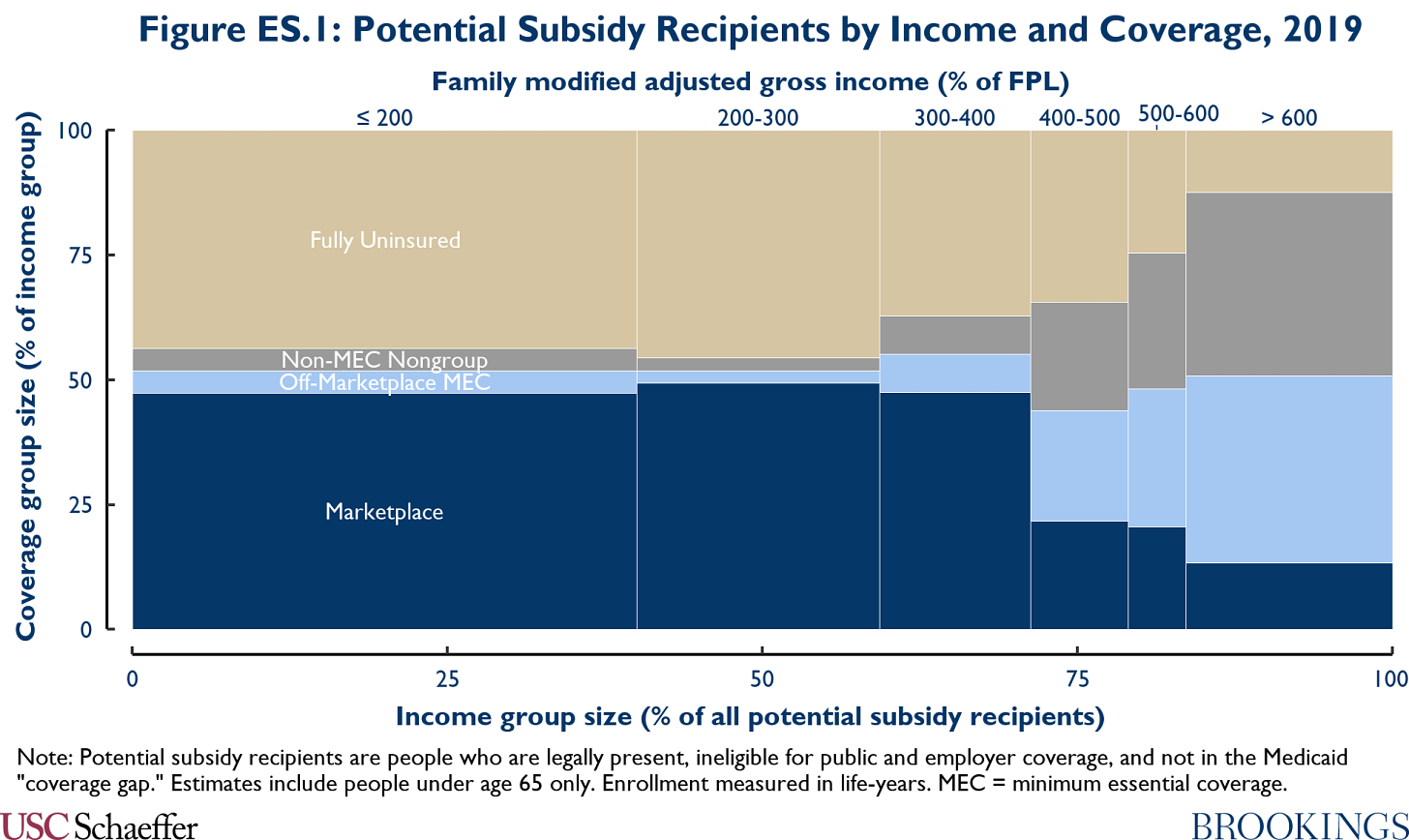

What do enrollees look like by income? Matt Fielder of The Brookings Institution estimated that using 2019 data. Americans without an employer or public plan under 400% of the poverty line almost completely forgo off market insurance in favor of Obamacare with almost half uninsured. For Americans above 400% of the poverty line without an employer or public plan, they are far more likely to be insured, but they almost entirely rely on off market insurance. And in many cases, that insurance would not satisfy minimum coverage requirements under the ACA. By limiting Obamacare subsidies to people under 400% poverty, the wealthy are incentivized to shop elsewhere for cheap coverage. The additional subsidies from ARPA may change that, as well as making health insurance more affordable for people below 400% poverty that may consider Obamacare plans too expensive.

Who’s still uninsured?

As of 2019, about 29 million Americans were still uninsured. The ACA cut the uninsured rate in half, primarily through the Medicaid Expansion and a significant portion through Obamacare. But as Matt Fielder’s analysis suggested, many people that qualify for Obamacare go uninsured. The same is true of Medicaid to a lesser extent. In fact, nearly half of the uninsured population either qualifies for Medicaid or could find at least a free Bronze plan on Obamacare, especially after ARPA subsidy enhancements. And still more qualify for some Obamacare subsidies. Of the 29 million uninsured in 2019, few wouldn’t have qualified for aid now. In total, Kaiser Family Foundation estimated 2.2 million people are stuck in the Medicaid gap, 3.9 million are ineligible for aid due to citizenship status, 3.5 million turned down an affordable employer offer, and 1.1 million went uninsured rather than purchase Obamacare without subsidies (this group is high income on average).

By age, this population is disproportionately young adults. They are also mostly employed full time, and are disproportionately Hispanic and Non-white.

I’ve written about how administrative burdens and other issues make young adults more likely to go uninsured. One of the key ones being choice overload. Rather than choosing between coverage or no coverage, people have to choose between dozens of plans between or even within metal levels. Insurance companies will even offer multiple plans within the same metal level with varying premiums, deductibles, copays, coinsurance, and out-of-pocket maximums. You can also choose if you want to add dental coverage or not. With so many decisions to make, people may put it off or simply not enroll. It’s a complicated process, and that’s without even considering networks.

So, what’s the solution?

There’s no shortage of solutions, and their own problems. You might claim that we should just have a public plan like Medicaid, but 7 in 10 Medicaid enrollees are covered by private managed care, and there’s a collection of plans to choose from there too. The main difference between Obamacare and Medicaid Managed Care (other than the reimbursement rate) is that Medicaid uses auto-assignment for beneficiaries that choose a plan. That and Obamacare asks you to guess what your income will look like next year rather than just say what you currently make. Medicaid mostly doesn’t have premiums, but you do see that in some people with CHIP, and taxes are a common revenue source outside that.

Interestingly, some people think we should just offer Medicaid with income-based premiums. That could work, but Medicaid reimbursement rates are very low, causing network issues. Additionally, any expansion of Medicaid would likely run into the same problem as the Medicaid Expansion from the ACA. Others have said we should simply lower the Medicare age, but Medicare comes with premiums as well (sometimes less generous than the ACA) and it’s only easy because premiums are deducted from Social Security like Employer insurance premiums are deducted at payroll. Medicare for All advocates have said we should simply remove premiums and have everything get paid for with taxes. That could also work, but remember than 1 in 5 Obamacare enrollees are self-employed. They already have to track their own taxes and premiums and that doesn’t help them much. Administratively, the improvement is minimal. The real benefit there comes from eliminating inequities in insurance types like Medicaid vs employer insurance, but that fight is difficult thanks to the politics of health care.

Considering that both Medicaid and Obamacare are mostly handled by private companies (with a significant number of Medicare enrollees as well), some CHIP enrollees have premiums, many Employer plans and Medicare have enrollee-side premiums, maybe the way to reduce the uninsured rate is to make the Obamacare market function a bit more like Medicaid, Employer insurance, and Medicare. Allow for auto-assignment, reduce the number of plans offered to avoid choice overload, avoid administrative problems like the subsidy cliff and Medicaid gap, make premiums as easy to pay as possible, then cut the costs of care and reduce plan inequity via all payer like Maryland or Germany. Or just do single payer. If you can pull it off.