ERISA, Third Party Administrators, and Self-funded Plans: America’s Primary Insurance Scheme

Locking you in and taking away guard rails, what could go wrong?

In your every day political discourse, we spend a lot of time talking about our government-run or government-regulated insurance schemes: Medicare, Medicaid/CHIP, the VHA, or the ACA marketplace (AKA “Obamacare”). Rarely, we will dip into employer insurance, employer mandates, and the group market. However, all of this ignores the way most employers offer health insurance to their employees – self-funded health plans. These plans are subject to the lightest regulations at the federal level, and are barred from state level regulation by design. And even though they are managed by insurance companies via third party administrator (TPA) set ups, your employer manages most of your health care; even if you aren’t aware of it. That’s the topic of this week’s post.

Refresher

If you need a refresher on how employer insurance came to be, you can read it here. Employer insurance was developed almost by accident as a result of the Stabilization Act of 1942. In order to prevent inflation during World War Two, the government set a series of price controls and wage caps for employees. As a concession to employers and unions, benefits were exempt from these caps and were untaxed. Later, during the Eisenhower Administration, this change was made permanent. The untaxed status of employer health care premiums was woven into the fabric of the American safety net. Many employers also helped their employees cover the costs of these plans by either paying for all or the vast majority of these premiums. Today, the typical employer will cover over 80% of the costs of their employer health insurance plan.

This was modified over the years and now, as a part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), employers with more than 50 full-time equivalent workers must offer employer insurance to their full-time employees with a minimum actuarial value of 60% (equivalent to a Bronze plan), or face penalties. Employees then are unable to shop for subsidized Obamacare, they are effectively “firewalled” in this marketplace. This didn’t seem to drastically change the number of firms offering employer health insurance though, as seen below.

If employers opt for traditional group health insurance, then they would also be required to offer the essential health benefits created by the ACA, but there was a way around this. If plans offered by the employer were “self-funded”, then the employer would only need to meet the “minimum value” requirement of 60%, meet insurance affordability requirements for their enrollees, and offer some basic free preventative care. Otherwise, they were free to modify plans as they saw fit. This is where a not so well-known law, by the average American, comes into play.

ERISA

Employer benefits continued to grow over the years since the Stabilization Act of 1942 and Eisenhower’s legitimization of it, with regulations varying by state. In an effort to standardize the framework, President Ford and Congressional Democrats worked together to pass the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). ERISA set up a common federal framework for employer pensions, retirement plans, welfare, health plans, and more. The focus was on pensions and retirement plans, but its effect on America’s health insurance framework is still being felt today. For health plans, it set up requirements for fiduciaries, reporting and disclosure requirements to ensure plan funds were not misused, and requirements regarding enrollee access to information on their plans and rights. It was further regulated in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) to bar offers and premiums based on health status as well as further requirements from the ACA, but by in large it had a deregulatory effect. While most federal laws act to set out minimum requirements, like minimum wage laws, ERISA instead preempted state laws and barred states from regulating further than ERISA, even when ERISA did not enact clear statutes or regulations.

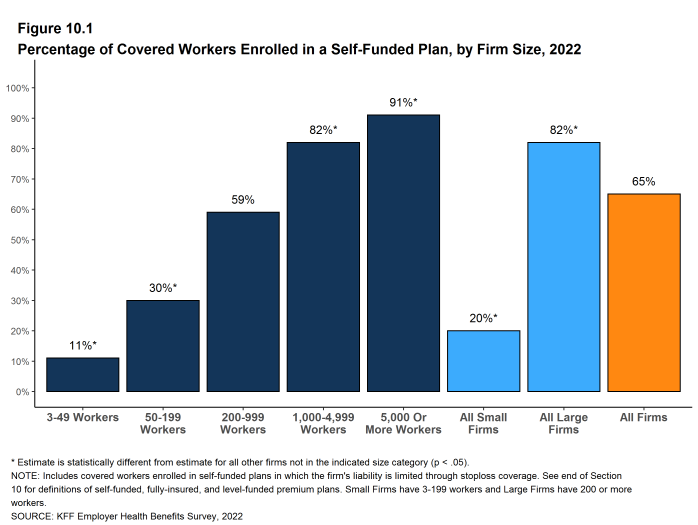

ERISA covers 65% of the 155 million Americans with employer sponsored health insurance plans. And this federal preemption and lack of regulation can create serious problems. Because of ERISA, states have been hamstrung from creating All Payer Claims Databases to get a system of transparent reimbursement insurers pay, from directly regulating insurance copays for services, for creating their own essential health benefits for all insurance types, or even making single-payer systems near impossible to create. There have been recent successes against ERISA preemption like with regulating PBMs rather than self-funded plans themselves, surprise billing laws, or directly regulating hospital prices themselves, but ERISA is still a large fundamental barrier for states when it comes to acting on their own to regulate the insurance industry.

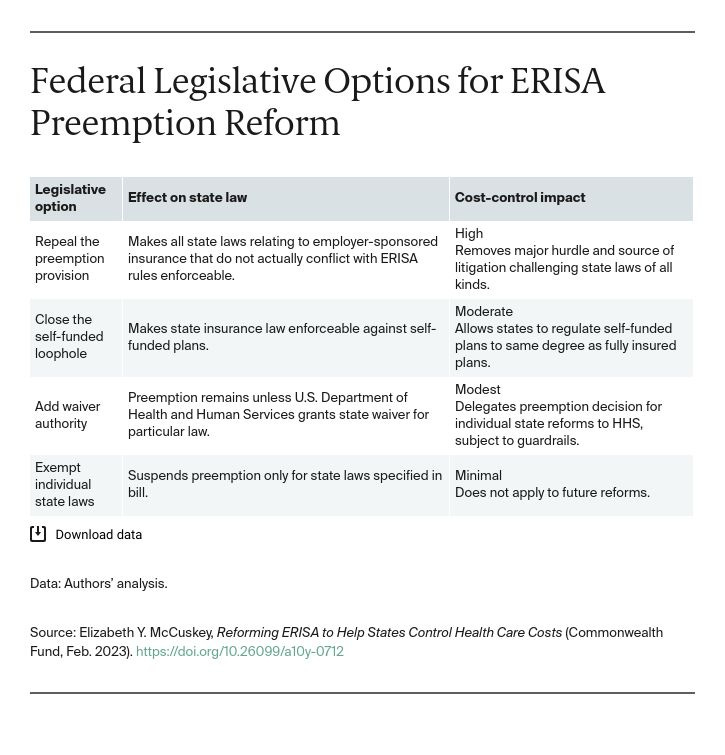

Currently, no pathway around ERISA exists where its domain has been made clear by the courts. However, there are several proposals to modify ERISA in order to allow states more discretion in regulating markets: repeal the preemption provision entirely, close the self-funded loophole, add a state waiver authority, or add specific domains to state authority. These would affect state ability to regulate self-funded plans to different degrees, but all would give states more control over their own markets. Until then, states will have to settle with regulating the individual market, the fully insured market, and modifying their Medicaid programs; or finding creative ways around the law on regulations like PBMs or real prices.

Self-funded Plans

So, what exactly are self-funded plans? They are when an employer chooses to self-insure the costs of medical care for their employees rather than purchase a fully insured group plan from an insurance carrier like UnitedHealthcare, Aetna, etc. While the premiums for a fully insured plan go to the commercial insurer’s larger risk pool that the insurers use their premiums to pay providers with, a self-insured plan comes fully from the employers own reserves. Employers will still collect premiums from employees and set aside funding of their own, but the costs are calculated only from the health care claims that this group of employees creates from their health care needs. These self-funded plans don’t have to cover the ACA’s essential health benefits, don’t have to meeting medical loss ratio requirements, and don’t have to follow the ACA age band rule for older enrollees capping premiums at no more than 3 times what younger enrollees are charged.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 65% of employees with employer plans are covered by these self-funded plans, though this is most common at large firms. And the share of self-funded plans has been slowly growing over time. Self-insured plans also vary regionally, and are more common in the South than the West Coast.

Because costs of claims can sometimes be very expensive, like if an enrollee is diagnosed with stage four cancer and requires extensive treatment, self-insuring employees can be risky for employers. Therefore, most employers purchase Stop-Loss Coverage (i.e. reinsurance) to protect themselves from these more expensive claims.

Otherwise, self-insured programs are far less well-regulated than traditional insurance. This allows employers access to overall claims data, and they may try to use employee incentive programs like screenings or fitness programs to encourage employees to lower their health care costs. They can even offer employees money towards their Health Savings Account or money off their share of premiums as an incentive. In the individual or group market, the benefits to the employer would be minimal because of the greater risk pool, but it can offer a real way to improve a self-funded risk pool.

TPAs

While ERISA created a system where employers self-fund their health plans, it authorized them to create arrangements with TPAs like health insurance carriers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). This allows employers to create relationships with subsidiaries of health insurance carriers that can process claims, adjudicate claims, give self-funded plans access to insurance company networks and rates, data analytics, easier relations with brokers, and help them review options with stop-loss coverage. This helps companies HR departments more easily manage their health care plans for their employees. It effectively gives them a path towards something closer to a fully-insured plan without the standard package (and state regulations) that go along with them.

Conclusion

This might sound like a good way to give employers more flexibility to set their own benefits, but these self-funded set ups are sparsely regulated as I have mentioned several times. There is no law mandating benefits other than basic coverage requirements under laws like HIPAA or the ACA. There is no requirement that self-funded plans purchase stop-loss coverage to protect themselves from very expensive cases. There is no requirement that employers prove they have the resources to self-fund before they do so. And TPAs can fall into the same sparsely regulated and managed landscape that self-funded plans and PBMs themselves do. In effect, ERISA and it’s lack of proper modifications in the decades since its passage have given employers a way to try to save a buck by cutting corners with their employees. And without federal modifications by Congress, there’s little states can do to protect their residents from poorly managed self-funded insurance plans. Finally, while fully insured plans can still be inadequate, they at least must follow all of the same regulations as the individual market, must follow all state regulations, and benefit from creating larger risk pools rather than allowing employers with healthier employees opt-out of the risk pool to save themselves money at the cost of people that work at different firms. Granting larger companies greater resources and opt out via self-funded plans could very well create a bias towards these larger companies that could harm competition in the long-run.