Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Middle Men for the Middle Men

The Introduction

By now, you’ve probably heard of health insurance and the various programs that regulate and provide health insurance for Americans. However, benefits for prescription drug coverage are often managed by a separate entity that health insurance companies contract out to called Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). PBMs negotiate with drug manufacturers for discounts and rebates on their prescription drugs and create what are called formularies of FDA approved drugs their enrollees can access. They provide prescription drug coverage for as many as 275 million Americans as a part of their health insurance coverage in contracts with employer coverage, Obamacare, Medicaid managed care, and Medicare Part D or Medicare Advantage. One estimate says PBMs can save enrollees and payers 40%-50% on the cost of drugs alone, or $1,040 per person. This business model pays well, with $315 billion in revenue each year.

PBMs typically set up their coverage into four tiers ranked 1-4, but they may opt for a slightly different model as well. In the typical set up, drugs are placed into the tiers for generic drugs, common brand names and preferred drugs, non-preferred drugs, and unique or high-cost drugs. Copays rise as drugs reach higher tiers, and the highest cost drugs may use a coinsurance set up instead of a flat copay so that enrollees share a much more significant portion of the cost.

Do PBMs skim off the top?

Drugs are placed on different tiers both as a result of their real cost and via the negotiations PBMs have with drug manufacturers. If a drug manufacturer agrees to a discount or rebate to the PBM, then they may be listed on a lower tier as a result and gain an advantage over their competition. Theoretically, this may allow PBMs to pass savings along to enrollees and the health insurer in the form of smaller copays, and lower charges to the health insurer that can lead to reductions in premiums. However, this creates an opportunity for the PBM to increase revenue instead of sharing savings in a few ways.

First, PBMs can rely on rebates instead of discounts. While discounts are reduced at point of sale, rebates can be cash paid to compensate for the cost of a drug purchase. So the list price can be high even though the de facto price is lower. If a PBM opts for rebates instead, they can directly receive cash for a certain drug being used by a member. And while health insurance is regulated to spend a certain amount of revenue on health care called Medical Loss Ratios, PBMs are held to no such standard and are not required to share any rebates they may receive from a drug manufacturer. Therefore, they can negotiate a large rebate from a drug manufacturer, and can pocket a disproportionate share of it rather than passing through savings to enrollees or the health insurer. A study suggested 91% of these rebates were passed through to insurers in 2016, but smaller health plans reported not receiving a portion of these rebates. And because of the lack of transparency around these rebates, insurers may be unaware of the specifics of these deals.

Additionally, enrollees only know drug copays and tier lists, so they may unwittingly be choosing a drug that is more expensive than another option because its copay is lower, leading to higher premiums and medical inflation over time. PBMs also may use what is called “spread pricing” where they charge health plans more for a generic drug that what they paid the pharmacy for the drug, keeping the difference as a nice profit. Similarly, PBMs can use what is called a “claw back,” where the enrollee copay is higher than what the PBM pays for a drug. The PBM then takes the difference back from the pharmacy. In Ohio, PBMs for Medicaid enrollees used spread pricing to collect another $225 million from the state, nearly a 10% mark up. In some states, PBMs even make pharmacies sign so called “gag rules” that prevent them from telling patients when a drug would be cheaper without using their insurance. Or they could simply refuse to cover certain drugs.

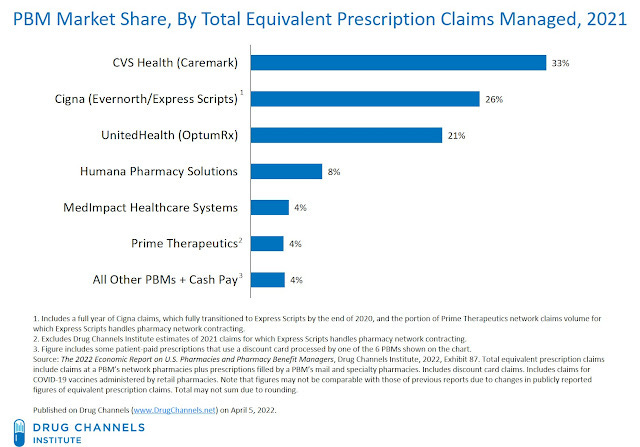

Just like the rest of the health care industry, PBMs have been experiencing problems of market concentration and vertical integration. The top three PBMs control 80% of the market, and are owned by CVS, Cigna, and UnitedHealth Group. Some of these companies also own health insurance companies, clinics, pharmacies, and dip their toes into innovation. In those cases, a PBM may find itself in the position of having an incentive to give preference to its own pharmacies and reduce its prices for competitor pharmacies in areas where they are the dominant PBM. If a small health insurer is a competitor but needs to use their PBM, a company has an incentive to not share their rebates or engage in spread pricing to ensure the health insurance offered by their corporation hold an advantage in the market thanks purely to their domination in the PBM market. This can all lead to less competition and higher prices for everyone.

Potential Solutions to these problems?

Many of these issues are quite well known among policymakers, and several states have been trying to enforce stricter regulations on PBMs. Some districts, like DC, ban “gag rules. Others may want to eliminate spread pricing, force transparency on how rebates are shared with enrollees and insurers, and force a type of Medical Loss Ratio on PBMs to ensure savings get passed to consumers. The free market is even playing a role with entrepreneurs like Mark Cuban going around PBMs and insurance to sell drugs directly to consumers at a reduced priced for a small profit, the Cost Plus Drug Company. The Congressional Budget Office Estimated the federal government would save $1 billion over 10 years from banning spread pricing in Medicaid plans, before accounting for state and consumer savings. This is a fairly small amount, but could be a low estimate, especially considering the prevalence of spread pricing in private plans and if spread pricing was banned in all plan types.

The basis of the Inflation Reduction Act was to allow Medicare the ability to negotiate the price of certain drugs with a penalty based on the wholesale price, or at least tie some drug price increases to the cost of inflation. This should mostly only affect Medicare, but it is a step towards further regulation on the industry. Some countries, like France, contract directly with manufacturers and pay for drugs based on the cost of production and value to consumer, and price accordingly to avoid being the highest priced drugs in the region. However, assessing value to customers unilaterally may be controversial. Measurements like quality-adjusted-life-years (QALYs) have come under fire for not properly accounting for extending life in situations where a patient still has a terminal diagnosis and requires care. Regardless, something like direct government regulation and setting of prices would be one way to significantly curb the cost of prescription medications for consumers.

Those aren’t the only choices policymakers have. There is also a policy tool called “reference pricing”. In the typical PBM model, drugs are listed on tiers with copays loosely related to the real price of a drug. Tier 1 may be $10-$20, Tier 2 $25-$50, Tier 3 $50-$100, with the possibility of a coinsurance model covering a percentage of the drug for the most expensive drugs. Within tiers, there is no incentive to go for the cheaper drug. In reference pricing, one drug for a given condition acts as the baseline for all the other drugs. If a drug within a tier is more expensive, the enrollee must cover the difference between the reference drug and this drug. One employer insurance model utilized this model and found a 14% reduction in costs, though 5.2% of expenses were shifted to enrollee cost-sharing. This is a potential way the US can rein in pharmaceutical spending, just as several other countries like Germany already use.

California is planning to go a step further than some of these solutions by getting directly involved in the production of insulin to lower costs for consumers. Just like with public insurance, public provision of a good is another way the government can save money for its citizens.

Conclusion

Just like how America delegates private insurers to manage our hospital and medical insurance, PBMs have found their niche managing our prescription drug coverage for insurers, employers, and the government. And while the focus in the Affordable Care Act was on the relationship between insurers, patients, and providers; PBMs came away largely untouched by new regulations. But a new dawn may be breaking. States have begun to regulate PBMs on their own, and the Supreme Court has ruled that ERISA, the law that preempts many state regulations on self-funded health plans and employer benefits, does not apply to PBMs. States are free to regulate PBMs as they see fit. With the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act to control some drug prices, and states free to regulate these middle men, maybe there is an opportunity for America to bend the cost curve on prescription drugs. By regulating the middle men, or even bypassing them entirely.