Medicare: The Basics of Design, Coverage, and Financing

Medicare, the favorite American health insurance program of progressives. A program that covers 65 million Americans ages 65 and older, and those with End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD), ALS, or have received disability insurance payments for two years. It is our largest single health care program in terms of spending and our second largest in terms of enrollees after Medicaid/CHIP’s nearly 90 million enrollees. Some people claim that Medicare is the closest thing America has to single payer public insurance, and expanding its coverage to everyone in the United States (and eliminating out of pocket costs) is the ideal way to achieve universal health coverage. But how is it actually designed? What does its coverage look like? And how is it financed?

Design

Medicare is a federal series of programs split into four parts and private supplemental programs called Medigap. Medicare Part A, Medicare Part B, Medicare Part D, and privatized Medicare Advantage (AKA Part C).

Medicare Part A was designed for inpatient hospital insurance that will cover hospitalization, inpatient surgery (oftentimes requiring multiple day stays in a hospital), inpatient rehabilitation facility stays, skilled nursing facility care, home health care, and hospice care. Medicare Part B was designed as medical insurance. It covers doctor’s visits, outpatient care and surgeries that have short stays or no stay, home health care, durable medical equipment like wheelchairs, and preventative care like screenings and vaccines. Some drugs can also be covered by these programs, like during hospitalizations. Medicare Parts A and B are publicly run government benefits, but like much of the government, it is run by private contractors via Medicare Administrative Contractors. These both started in 1966 after the Social Security Act of 1965.

Medicare Part D is for prescription drug coverage that started in 2006 after implementation of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. Unlike Parts A and B, this program is not government run. Enrollees must select a plan from a series of regulated private providers.

Medigap is different from Parts A, B, and D in that it is only meant to supplement, not replace, these programs and its plans entirely private and voluntary without coercion. Medicare Parts A, B, and D do not come with out-of-pocket maximums and come with deductibles. Medigap can be purchased for an additional premium to provide additional cost-sharing support and even an out-of-pocket maximum. However, it cannot cover comprehensive dental/vision/auditory care. Medigap is split into ten plan types as standardized by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. While Medicare’s parts are controlled by the federal government, Medigap and access to it is regulated by the states as well. This can create significant variance by state, though in most states you only gain guaranteed issue without underwriting at age 65. People that qualify before 65 often do not have guaranteed access to Medigap. People in Medicare under 65 qualified via disability, so you would hope that they would be dually eligible and avoid this problem. But a gap exists here because Disability Insurance qualifies you for Medicare, while Supplemental Security Income (SSI) qualifies you for Medicaid. SSI being means-tested, someone with a qualifying disability may still be denied for being too high income or having too many assets (typcically limited at $2,000). One in ten people on Medicare have traditional Medicare and lack any supplemental care. These people are disproportionately lower income and disabled.

Medicare Advantage is a privatized version of Medicare, created in its modern form by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, that combines the coverage for Parts A, B, and D in a single plan. It can also cover comprehensive care for dental/vision/auditory care, and can supplement that basic care like Medigap does. This is all done in a single plan rather than keeping track of the different traditional Medicare programs. Additionally, while nearly all physicians and hospitals take traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage uses HMOs and PPOs to create a narrower network of providers. This is done so the company can take their capitated payment from the government and keep some of what they don’t spend for profit. Regardless, Medicare Advantage costs the government more per person than traditional Medicare. As much as 42% of Medicare enrollees used Medicare Advantage in 2021, and its share is growing.

The amount of choice, like Obamacare, can be overwhelming. The average beneficiary has 39 Medicare Advantage plans, around 25 Part D plans, and ten different kinds of Medigap plans to choose from.

Coverage

Signing up for Medicare typically starts a few months before you turn 65, unless you qualify via ESRD. In some cases, you may qualify for a delay if you have employer coverage. Because some people have employer insurance and/or have a tax-free Health Savings Account (HSA), they may choose to delay signing up for Medicare Parts A or B. Medicare Part A doesn’t have premiums if you have 40 quarters (10 years) of earnings, but premiums otherwise could be anywhere from $279-$499/month. That charge means some people may get cheaper premiums on employer coverage. Medicare Part B has premiums starting at $170.10/month, with rates rising by income as seen below. Part D varies, but likewise has graduated surcharges by income added on to plan premiums.

As long as someone signs up within 8 months of losing their employer insurance, they will not get a late penalty. If they do not sign up by the deadline, they may get penalized. The penalty for Part A is a 10% surcharge for twice the time you delayed coverage. For Part B, the penalty is a permanent additional 10% surcharge for every year you delayed coverage. For Part D, the penalty is a permanent additional 1% surcharge for every month you delayed coverage. These coverage requirements can be fulfilled with the purchase of a Medicare Advantage plan. Interestingly enough, these penalties function in a similar way to the ACA’s Individual Mandate before it was set to $0. Though the Individual Mandate was costlier.

Traditional Medicare also comes with deductibles and cost sharing. Medicare Part A has a $1,556/year deductible that must be paid each year before coverage kicks in. For inpatient stays, the first 60 days are fully covered by Medicare Part A after the deductible is met, days 61-90 cost $389/day, and days 91-150 cost $778/day. However, Medicare comes with only 60 reserve days after the first 90 days of hospitalization for the entire life of an enrollee. Once hospitalized for 90 days and after all reserve days are used, all costs are on the enrollee unless they have a Medigap plan, private long-term care coverage, or coverage via Medicaid. Part B has a $233/year deductible and 80% of costs are covered after the deductible is met. Most Medicare Part D plans have deductibles. Without a Medigap plan, a Medicare Advantage plan with an out-of-pocket maximum, or other coverage like Medicaid, there is no maximum an enrollee can pay out of pocket. For this reason, many people opt for Medicare Advantage to eliminate premiums after Part B rated premiums to get an out-of-pocket maximum and dental/vision/auditory coverage not covered by traditional Medicare or Medigap.

While Medicare Parts A, B, and D do not use underwriting, the same isn’t true of Medigap and Medicare Advantage. When you become eligible at age 65, you have a six month period to sign up for Medigap or Medicare Advantage without underwriting. If you choose to go without Medigap while electing to have traditional Medicare, but change your mind, Medigap providers can assess your health status prior to enrollment. The same is true if you choose Medicare Advantage and want to return to traditional Medicare and purchase Medigap. However, you are given a 12 month trial period on Medicare Advantage without this occurring, and you can avoid this if you move and lose access to your Medicare Advantage plan or the plan is discontinued.

Because Medicare premiums can be hard for poor seniors to afford, Medicaid funding can be used to pay for Medicare premiums. However, these programs come with income and asset tests. And because they are run via Medicaid, they vary by state.

Financing

As you may imagine, Medicare is split into several parts, so it’s financing is different between the parts. Medicare Parts A and B are funded by two separate trust funds. Medicare Part A has the Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund, and Parts B and D have the Supplemental Medical Insurance (SMI) Trust Fund. The SMI Trust Fund mostly exists to smooth out coverage during revenue short falls and is smaller than the HI Trust Fund by nature. The HI Trust Fund is almost entirely funded by a 2.9% payroll tax split evenly between employers and employees with some additional funding from people that must pay premiums, interest from the trust fund, taxation of Social Security benefits, and transfers from states. There’s also a surcharge of 2.35% for earnings past $200,000 for an individual and $250,000 for a couple. Part B is funded mostly via general revenue from a series of federal taxes, a quarter from premiums, and some transfers from states and interest. Part D is funded mostly with general revenue with a smaller share of premiums than Part B and a larger share of transfers from states. The exact breakdown can be found below.

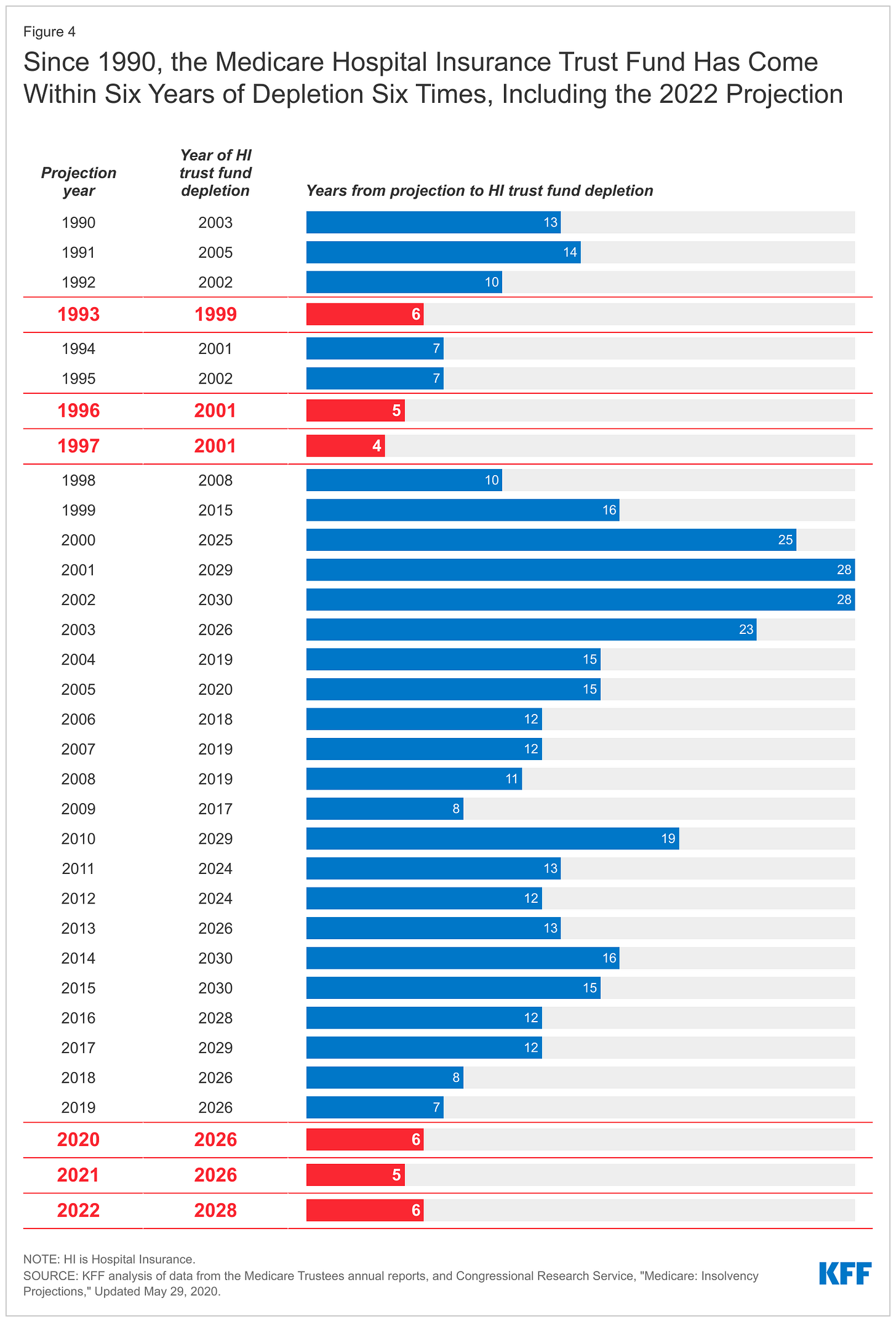

You may have heard that the Medicare Trust Fund faces a crisis from insolvency. When people discuss this, they tend to specifically mean the HI Trust Fund for Medicare Part A. The 2022 Medicare Trustee Report projects that the Medicare Trust Fund will go insolvent by 2028, while the CBO projects that it will go insolvent in 2030. If that happens, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will have to adjust its payment rates to ensure they can pay all the required costs of the program. At present, the CBO projects the tax revenues would only be able to cover 92% the costs of the current program, and payments would have to be reduced to meet the inadequate revenue. This would be a substantial drop to hospital reimbursement, but still quite higher than Medicaid reimbursement rates.

Congress could address this shortfall in several ways. The Medicare Trustees estimate raising the payroll tax by 0.7 percentage points to 3.6% would be enough to ensure long term sustainability. Other suggestions include: raising the Medicare age (though this would increase national health expenditures and raise costs for people that aren’t on Medicare that otherwise would be), increasing the later Medicare surcharge amount, allowing for an injection of general revenue, passing comprehensive immigration reform to increase the tax base, increasing the usage of bundled payment models and accountable care organizations, redirect the Net Investment Income Tax to the HI Trust Fund, reduce Medicare Advantage benchmarks to save money, limit growth in drug spending, etc. Many of these plans can come in bundles that could extend solvency by 9 years or more. It should be noted the HI Trust Fund has had brushes with insolvency before. Each time with Congress acting to extend its lifespan. With demographics and the health care industry of the country everchanging, periodic action to pay for this program is expected. The only ways to avoid this would be to either eliminate the Trust Fund system, or give a non-political body the ability to independently respond to the problem, though the appetite for this in Congress seems lacking.

Conclusion

So, there you have it. If you thought Medicare was a single program, it is really more like four with supplemental private plans and some aid from Medicaid being possible. The government version of Medicare can’t cover dental/vision/auditory coverage and Medigap is constrained from it as well. Medicare has no long-term care coverage, and you can both get it earlier in special circumstances or delay coverage (or delay coverage for Part A, but no Part B, and vice versa). You can even refuse to buy it, but it comes with penalties if you opt for it later. It is both public, private, and offers private supplemental plans. Its financing is completely different depending on part of the program it is. And finally, its coverage is much more fractured than other coverage in the US (but with much better cost controls) than the comprehensive plan without cost sharing talked about in the “Medicare for All” proposal. Regardless of the merits or faults of that proposal.