Medicaid & The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): The Afterthought and Backbone of America’s Safety Net

A very basic introduction to America's coverage for the poor

The Democratic health policy debate often focuses on building on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or doubling down on Medicare until everyone gets it, like Medicare for All. This pattern of chasing universal health coverage has gone on for decades, with progressives espousing the merits of federal Medicare and moderates talking about its “third way” to use government regulation to ensure quality in the private sector. All the while, Medicaid is the step-child that’s grown over the decades. So, what is Medicaid? How does it work? And how has it always been an afterthought despite its size?

Medicaid is a voluntary federal-state partnership to cover poor Americans. That’s different from Medicare, which is the federal program to cover elderly Americans aged 65 and older, and later people with End Stage Renal Disease and the disabled. Both Medicare and Medicaid were created as a part of the Social Security Act of 1965 as one of the crowning achievements of LBJ’s Great Society programs. As I’ve written in the past, Medicare was the compromise plan JFK tried and failed to pass after seeing Truman fail at achieving National Health Insurance in 1946. JFK was stymied by Congress for years, but LBJ was able to use the period after JFK’s assassination to pass a wave of liberal legislation. Though Congress had a general agreement that they should create a federal and essentially universal program for the elderly in their final years, they also realized that Medicare alone was not enough. It would not do enough to care for the poor that weren’t elderly.

The Origins and Expansion

In the years before the Social Security Act of 1965, Congress passed the Kerr-Mills Act of 1960. This was a federal-state matching program that was uncapped to created the Medical Assistance to the Aged (MAA) for very poor seniors aged 65 and above. The programs would be run by the states, and income and asset tests would be used to ensure the only target population was cared for. Though some expected this program to cover anywhere from 2 million to 10 million seniors, only about a quarter of a million seniors (less than 2% of seniors) got coverage by 1965, and only 40 states had agreed to it. Realizing they had to act for the non-elderly poor with the passage of Medicaid, but unable to pass some universal program like Truman wanted, Medicaid was born as a copy of earlier policy disappointments. It followed the voluntary uncapped federal-state matching program like MAA under Kerr-Mills, but did a couple things to incentivize compliance: generous matching rates, and ending the MAA program by 1969. However, it came with a catch. It was a categorical program. If states opted in, they had to agree to cover all the Americans eligible for Aid to the Blind, Aid to Families and Dependent Children (welfare), Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled, and make it available to anyone receiving assistance under any state plan approved for those programs. If a state elected to cover the medically indigent, it had to do so for all categories of aid and under comparable standards of duration, amounts, etc. Over time, original Medicaid covered disabled people through a variety of pathways: Supplemental Security Income (SSI) enrollment, medical necessity my paying income and assets to a certain level after medical expenses, higher levels if institutionalized, and higher levels for disabled people that work. This gets even more complex with varying rules in each state for all pathways.

Acceptance took years, but by 1974 the vast majority of states had signed up, and Arizona was the last to sign up by 1982. Though voluntary, it was generous enough for all states to agree eventually. And being given discretion past those initial welfare groups helped the medicine go down. This was further expanded in the 1980s so children had to be covered up to 133% of the poverty line, CHIP was added in 1997 and expanded in 2009 as a block grant to states to cover children past Medicaid, and of course the ACA expanded Medicaid in 2010 up to 133% poverty for all Americans (to match the earlier rate for kids) with a 5% disregard making the de facto limit 138% of poverty. Because of the Medicaid and CHIP expansions, about 4 in 10 children are covered by Medicaid/CHIP and the child uninsured rate is second only to seniors at about 5%. Although Congress tried to threaten states with losing all Medicaid money if they didn’t accept the ACA expansion, the Supreme Court decided it was an unenforceable mandate and states must voluntarily opt-in like original Medicaid and CHIP. While states all opted in to the bipartisan CHIP fairly quickly, 12 states still haven’t expanded Medicaid as of today (about decade after they have had to option to do so). Even still, for everyone that gained coverage from the ACA, 2 in 3 came from the Medicaid expansion. And Medicaid typically has fewer eligible enrollees going without coverage compared to the ACA marketplace. Part of that could be from retroactive enrollment, but being signed up for a plan when you only apply and don’t pick a plan can’t hurt either. For the marketplace, you can be given dozens of plans to choose from. A flood of choice. Medicaid doesn’t have the same problem.

It’s not as simple as Medicaid Expansion either. Medicaid expansion was all about expanding coverage to adults, parents and childless adults. Many expansion states and non-expansion states go further for children, pregnant women, and parents. For pregnant women, Medicaid eligibility ranges from 138% poverty to as high as Iowa’s 380% poverty. CHIP funds can be used for pregnant women, but not parents. And for children, CHIP eligibility can range from 175% poverty to 405% poverty. Though it’s more complicated because it is a block grant. Children in their first year may qualify at one income level and not the next year. States have a lot more flexibility with CHIP than Medicaid. That was part of the selling point. For some older children, eligibility can be as low as 138% poverty to 324% poverty thanks to variation in Medicaid and CHIP. And adults? For expansion state parents and non-parents, it’s typically 138% the poverty line. With Connecticut and DC going farther. For non-expansion states, they generally refuse to cover able-bodied adults at all. For parents, the threshold can be extremely low. In Texas, parents can only be covered up to 16% the poverty line.

The Federal-State Share

Now how generous was this federal share? For original Medicaid, the minimum Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) is 50%, but only 11 states get that. The other 39 states and DC get more generous rates; some more than 70%.

How exactly does this formula work? Like this (Taken from KFF):

If your state (or DC) has a nationally average per capita income, the FMAP will be 55%. Meaning the state will be responsible for 45% of the costs. And the FMAP is limited to no more than 83%. So, this rate was just extended for CHIP and the Medicaid Expansion, right? No. CHIP’s matching rate is set at 30% of the remaining rate after the state’s FMAP. So if they get the 50% FMAP (1 -0.50)*0.3 = 65%. The enhanced FMAP here cannot exceed 85%. And for the Medicaid Expansion the covered group past the population states covered pre-expansion FMAP was initially 100% and declined over time until stabilizing at 90% in perpetuity. In other words, the remainder of the people newly eligible up to 138% of the poverty line.

Now you might think because traditional Medicare doesn’t cover dental/vision/auditory care that the same must be true of Medicaid. But that’s not accurate. Many states offer some coverage in these areas. Only a few states didn’t cover dental care in 2019 (and Maryland has begun to expand services), 33 states and DC offer vision coverage, and 28 states and DC offer auditory coverage. Though coverage heavily varies by state. That’s a repeating story with the 51 different Medicaid programs. And that makes some sense with Medicaid. After all, Medicare and Medicaid were created when the focus was on hospital and medical coverage, expansion for things like drugs and hospice care came later.

Something else that sets Medicaid and CHIP apart comes down to premiums and cost-sharing. While Medicare Part B and Part D have premiums and all parts of traditional Medicare have substantial cost sharing (20% for Part A), these are nearly non-existent for Medicaid and CHIP. Only 4 States require premiums for Medicaid and only 1 requires cost sharing; never before the poverty line. For CHIP, 26 states have premiums and 21 have cost sharing, but often at around twice the poverty line for premiums or around the Medicaid cut off for any cost sharing. Medicaid is much more generous for out-of-pocket costs and premiums than Medicare or any employer plan you could find. There is a major drawback though. In order to save costs, state Medicaid programs have reimbursement rates set remarkably low. Just 72% of Medicare for all services or as low as 66% for primary care. As a result, while nearly all physicians take Medicare, a small number of physicians care for the vast majority of Medicaid patients and many only take a few at any time. And there’s stigma to being a Medicaid patient. Some people will mention being told physicians aren’t taking new patients once they say they have Medicaid coverage, or physicians openly will not take that coverage. When private insurance pays several times what Medicaid offers, its in a physician’s best interest to take as few Medicaid patients as possible. In fact, many state Medicaid programs try to address stigma by avoiding the word “Medicaid” at all.

Privatization of Medicaid

Finally, many people think of Medicare and Medicaid as clearly public insurance, but that’s not quite the case. In the 1980s and 1990s, state governments started delegating the work of their Medicaid programs to private Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) with capitated payments to cover their beneficiaries. This was an attempt to use the private sector to curb cost growth, just like was later tried with private Medicare Advantage. As a result, about 7 in 10 Medicaid beneficiaries are covered with a private MCO plan rather than a traditional government Medicaid plan. In fact, a majority of Medicaid spending comes from these MCOs. Just like how almost half of Medicare enrollees use Medicare Advantage. You can learn more about the transition to Medicaid MCOs here.

Filling in past policy holes

Aside from typical health insurance benefits, Medicaid also supplements other programs. As explained above, Medicaid enrolled beneficiaries of the Aid to the Blind and the Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled. As a legacy of this, long term care in the United States is handled by Medicaid. In fact, Medicare doesn’t cover long term care at all. In order to qualify for long term care on Medicaid, you have to meet an income test and an asset test at just $2,000. You have to spend your retirement, all private long term care insurance, and practically lose all possessions other than your house and a car. After that, Medicaid long term care can take effect. Some state may do more and may have home care they fund to varying degrees.

Medicaid also has some funding allocated to repay hospitals to caring for needy patients like the uninsured, or to help supplement the poor to help them pay their Medicare premiums. Again, that varies by state.

Conclusion

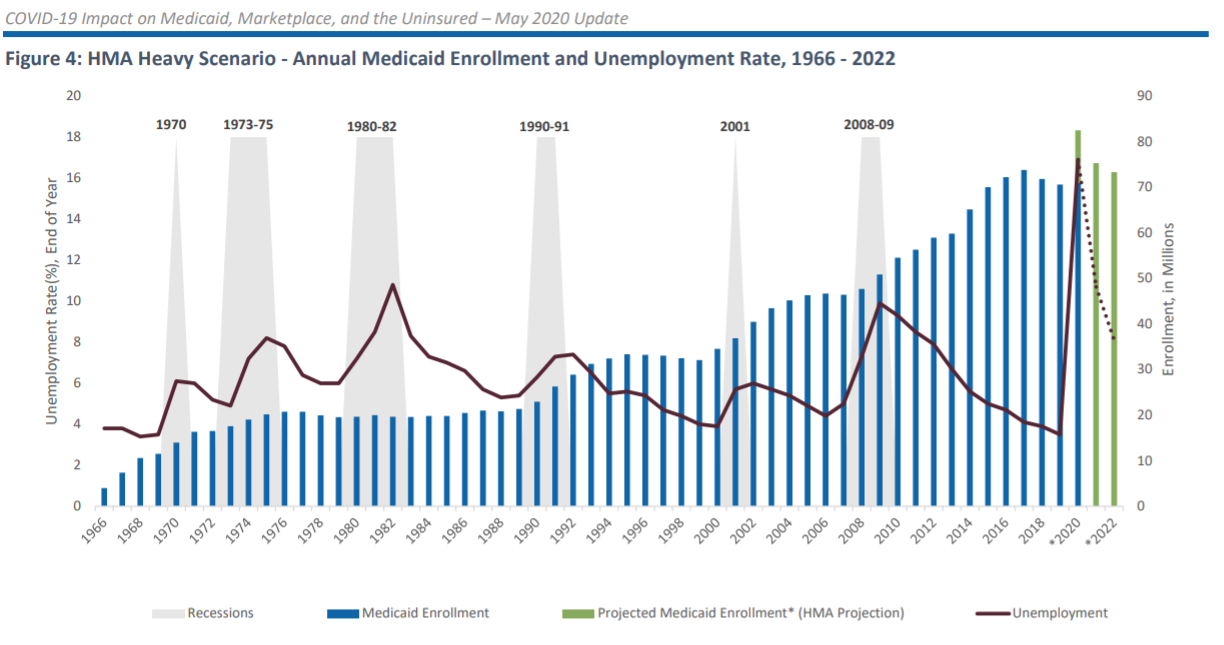

As a result of these partial expansions at the federal and state level over the years, Medicaid has proven resilient and able to grow over time. While Medicare covered essentially all seniors within a single year (a monumental achievement), Medicaid took a more gradual path. And as a result, its enrollment has grown from only 4 million in 1966 to 87 million in 2022. Outgrowing, and supplementing, Medicare along the way. America’s afterthought of welfare policy that turned into its backbone. And while some feared an explosion of uninsured rate from the COVID Recession, a result of our previous ties to employment insurance, the combination of Medicaid and the ACA marketplace ensured insurance coverage was mostly consistent.

(Graph taken from here.)